At the centre of this Māori value is the word whānau. As Māori we are very conscious of our kinship connections to one and other, and remain, to this day part of a network of families, sub-tribes and iwi. We articulate this sense of belonging in our pepeha. For the audience at hand, the pepeha locates us. It enables everyone to identify with us and who we are in relation to them.

John Rangihau introduced this concept to the machinery of government in his 1988 review of the then Department of Social Welfare Puao Te Atatū. He argued that, rather than bringing tamariki Māori into foster care, these children should be placed with whānau – the extended family. This seminal report influenced the shape of legislation that followed. Other government agencies also went on to develop their own bicultural strategies.

Thirty years on, whanaungatanga has assumed a broader meaning. It is defined in the Māori dictionary as ‘a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a shared sense of belonging.’ In the mental health and addictions field, the term has a number of applications.

First and foremost, whanaungatanga requires that practitioners engage with the whānau of tangata whaiora Māori at every stage of any intervention. The decision making should model a shared approach – family members should know what is happening and be at the centre of decisions being made about their future. The whānau will offer up insights and solutions that will help them become more self-managing and better able to use their strengths to care for their loved one. Developing this relationship with whānau is especially important when tangata whaiora exit services. For many, their whānau will be their most important source of long-term support.

Leaning into the new evolving meaning of whanaungatanga, the concept has other implications for the way we work as professionals. Organisations need to foster an environment of inclusion with a focus on relationships particularly with the whanau. Decision-making needs to be joined up, shared and multi-disciplinary. When all the dimensions of tangata whaiora wellbeing are considered, the best outcomes follow. There is no one solution for each whānau has a different set of circumstances. Clinicians could begin by inviting tangata whaiora and whanau to say what is important to them for the service to be successful.

It is important that we address tangata whaiora wellbeing across a range of domains. When everything is in balance, there is harmony. I don’t believe this occurs sufficiently in contemporary mental health and addiction services.

I see too, in the modern usage of whanaungatanga, room to address the diversity within tangata whaiora Māori. Takatāpui, for example, have support systems that extend beyond their biological whānau. We need to consider their needs, which may necessitate engagement with other takatāpui, and specialist organisations. Tangata whaiora with disabilities also need very specific types of support. Taking account of issues like this, means our expression of whanaungatanga is broader and more expansive.

It is a positive thing, whanaungatanga. It articulates a sense of belonging and connection for all of us. When we make this value part of our daily professional practice, I believe powerful change is possible.

Author: Wi Keelan, kaumatua and cultural advisor, mental health and addiction quality improvement programme

What research tells us

In August 2018, the Health Quality & Safety Commission conducted the national survey – Ngā Poutama Oranga Hinengaro: Quality in Context in mental health and addiction services. This survey was conducted to inform the future direction and focus of MHA quality improvement initiatives.

Thank you to the over 2,500 staff around the country who participated in this important survey. There were many statistically significant differences between ethnic groups and the national results.

Compared to national results, Pacific MHA staff were more likely to give a positive response across each of the 22 quality and safety culture questions. Māori MHA staff were also more likely to give a positive response across most questions. These responses evidence the implementation of whanaungatanga in services. We need to build on this positive foundation and promote whanaungatanga as a concept relevant to our work.

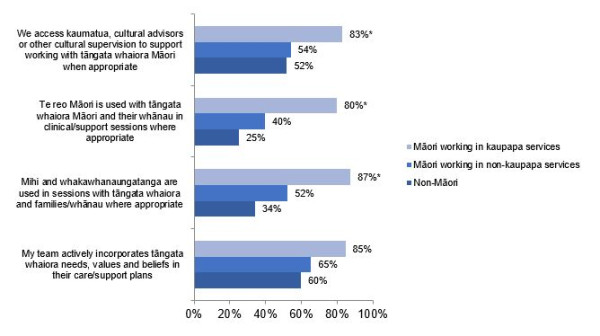

Positive responses to cultural competence questions among Māori working in kaupapa Māori services, Māori in non-kaupapa services, and non-Māori

Māori staff working in kaupapa Māori settings were more likely to give a positive response than Māori working in non-kaupapa settings – and non-Māori staff overall (see graph).

A graph showing Māori staff working in kaupapa Māori settings were more likely to give a positive response than Māori working in non-kaupapa settings – and non-Māori staff overall

* Statistically significant difference between Māori working in a kaupapa Māori service and Māori working in non-kaupapa Māori service.