To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Acute deterioration assessment

- Decision support

- Chest pain assessment

- Chest pain decision support

- Sepsis

- Acute deterioration decision support

- Responding to acute deterioration

- Treatment

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Acute deterioration is a sudden, clinically important, rapid change in the person’s baseline cognitive, behavioural, functional or physical health domains. In this case, ‘clinically important’ means a change that, without intervention, may result in complications or the death of the older person (American Medical Directors Association 2003).

Key points

- The broad concept of acute deterioration includes all causes of acute illness, from exacerbation of a chronic condition to a new undifferentiated (unknown cause) issue. It includes syndromes such as delirium and sepsis.

- Changes in health domains often occur before vital signs change.

- Vital sign changes may be late indicators of deterioration. Do not hesitate to call for help if you believe the person to be unwell.

Why this is important

Detecting acute deterioration in people living in aged residential care (ARC) enables registered nurses (RNs) to access the right treatment, at the right time, in the right place for older people living in their care (Daltrey et al 2022; Laging et al 2018). If acute deterioration occurs, frail older people are at higher risk of mortality and morbidity than their counterparts who are not frail (Clegg et al 2013; Kojima et al 2018; Stow et al 2018).

Implications for kaumātua*

It is important to take a holistic approach to assessing the impact of the episode of deterioration on kaumātua. This may include how they are feeling spiritually (a wairua), physically (a tinana), mentally and emotionally (a hinengaro). Kaumātua may experience whakamā (shame, embarrassment) about their deterioration and may not report symptoms to avoid burdening others.

It is essential to provide kaumātua and whānau/family with all the information they need to understand the approach to assessing and treating episodes of acute deterioration.

Support them by:

- including whānau/family in conversations

- providing opportunities for whānau/family to share their observations and insights, and valuing their input

- setting aside adequate time to discuss the matters with all parties involved

- thoroughly discussing and explaining decision-making about any changes in the plan of care (eg, escalation in care, medication changes, investigations).

See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment**

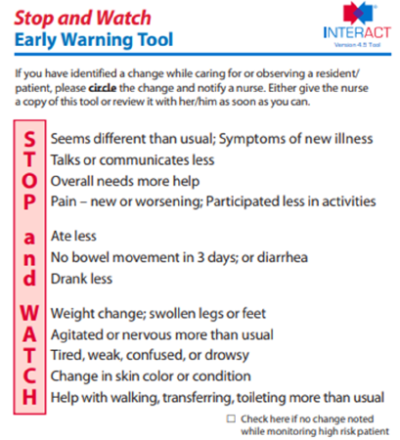

A standardised approach to identifying and responding to acute deterioration is recommended. Tools specifically designed to support RNs in ARC are limited. The most widely distributed caregiver tool for identifying deterioration is the Stop and Watch tool.

Reports on common patterns of acute deterioration in people living in ARC may help RNs identify and respond to acute deterioration (Daltrey et al 2022).

**Research is under way in New Zealand to develop a Deterioration Early Warning System for ARC (DEWS © Daltrey and Boyd 2022). The DEWS will support this guide once published.

Identifying deterioration

Care staff have the most direct contact with people living in ARC and are most likely to identify a subtle change from baseline. In ARC, where long-term relationships develop, noticing subtle changes is often described as ‘knowing’ something is wrong (Boockvar et al 2000; Sund-Levander and Tingström 2013). Care staff may notice something listed on the Stop and Watch tool or a change from baseline that is unique to the individual. Where they identify a change, the RN needs to assess it to determine its urgency and what response is required.

Stop and Watch early warning tool

The Stop and Watch early warning tool helps care staff identify and report specific issues (Ouslander et al 2009).

It is available as Pathway INTERACT® from the Pathway Health website after registering (Pathway Health nd).

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Role of the registered nurse

RNs have an obligation to assess issues that care staff team members and whānau/family report to them. They must also initiate a timely and appropriate response.

Assessing the situation

Assessment is complex. Subtle changes noted in the older person could be evidence of acute deterioration, an expected end-of-life process or an undisclosed social issue. Acute deterioration can be life threatening so the safest approach is to focus on confirming whether acute deterioration is present or not before considering other non-clinical causes of a changed presentation.

Responding and coordinating

New undifferentiated issues (those with unknown cause) need a diagnosis. Follow your facility policy to contact the correct health professional, eg, general practitioner (GP), nurse practitioner (NP) or urgent care.

Acute deterioration assessment

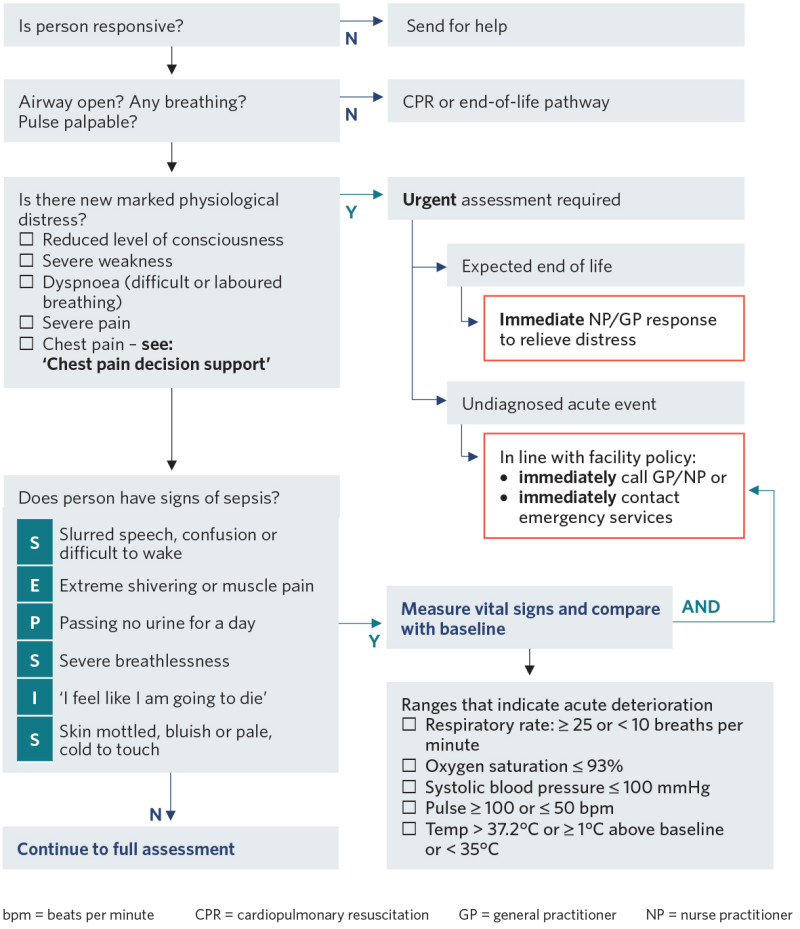

Rapidly and immediately consider life-threatening issues before completing a full assessment of acute deterioration. Where the condition is life threatening, you must call urgent services (NP, GP or ambulance, according to the protocol of your facility).

Decision support

Emergency screen

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

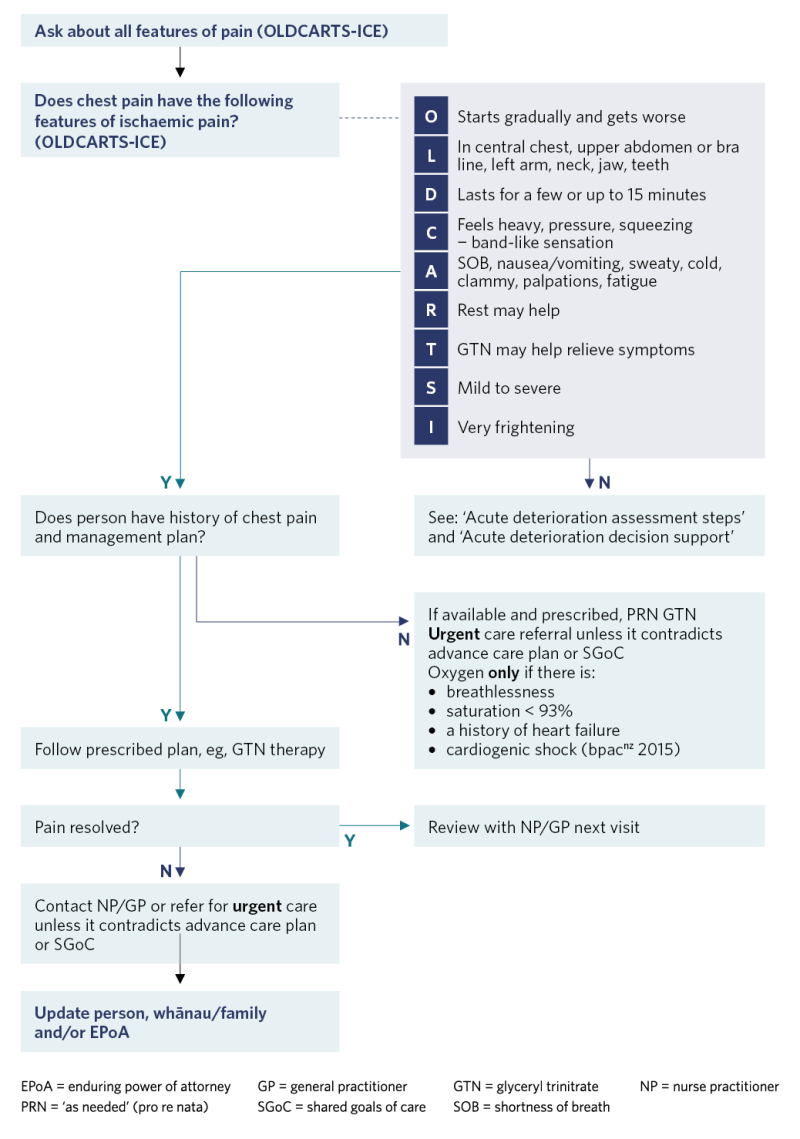

Chest pain assessment

Chest pain can have many different causes, but you should always investigate it. Frail older people with acute cardiac events may present with increased breathlessness (see the Approach to breathlessness (dyspnoea) | Tūngāngā guide) with or without chest pain. Use a framework to assess for cardiac chest pain (OLDCARTS-ICE).

- Onset: Does it start suddenly or gradually?

- Location(s) and radiation: Where is the pain?

- Duration: How long does it last?

- Character: What does it feel like?

- Associated: Are there any other symptoms?

- Relieving or aggravating: What makes it better or worse?

- Treatments: What treatments have been tried?

- Severity: How bad is it? What is the pain score?

- Impact, Coping, Expectation: What does it mean for the person?

Chest pain decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition caused by the body’s exaggerated response to infection that can lead to tissue damage, organ failure and death (Sepsis Trust NZ nd). Consider all people living in ARC who have an infection to be at risk of sepsis.

Tools for sepsis screening have not been validated for frail older people specifically (Daltrey et al 2022; Reyes et al 2018). However, the following tools may be useful to support decision-making. If the person has an infection and is deteriorating, get help fast (better to assume sepsis and be wrong than to be too cautious and miss sepsis).

Sepsis screening tools

Sepsis Trust New Zealand home-based screening

S: Slurred speech, confusion or difficult to wake

E: Extreme shivering or muscle pain

P: Passing no urine for a day

S: Severe breathlessness or breathing very fast

I: It feels like you are going to die (reported)

S: Skin mottled, bluish or pale or feels abnormally cold to touch

100:100:100 criteria

- Temperature (> 100°F) > 37.8°C

- Systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg

- Heart rate > 100 beats per minute

Quick sepsis-related organ failure (qSOFA)

- Respiratory rate > 22 breaths per minute

- Altered mental status

- Systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg

Sepsis treatment in ARC

Sepsis management in ARC is limited. It consists of oral antibiotic therapy, supplemental oxygen to keep saturation above 93%, maintaining fluid intake to about 1.5 L in 24 hours (or considering subcutaneous fluids) and pain management.

Sepsis has a high mortality rate, and early intervention is key. If a person is likely to need intravenous therapy, they will require rapid transfer to hospital.

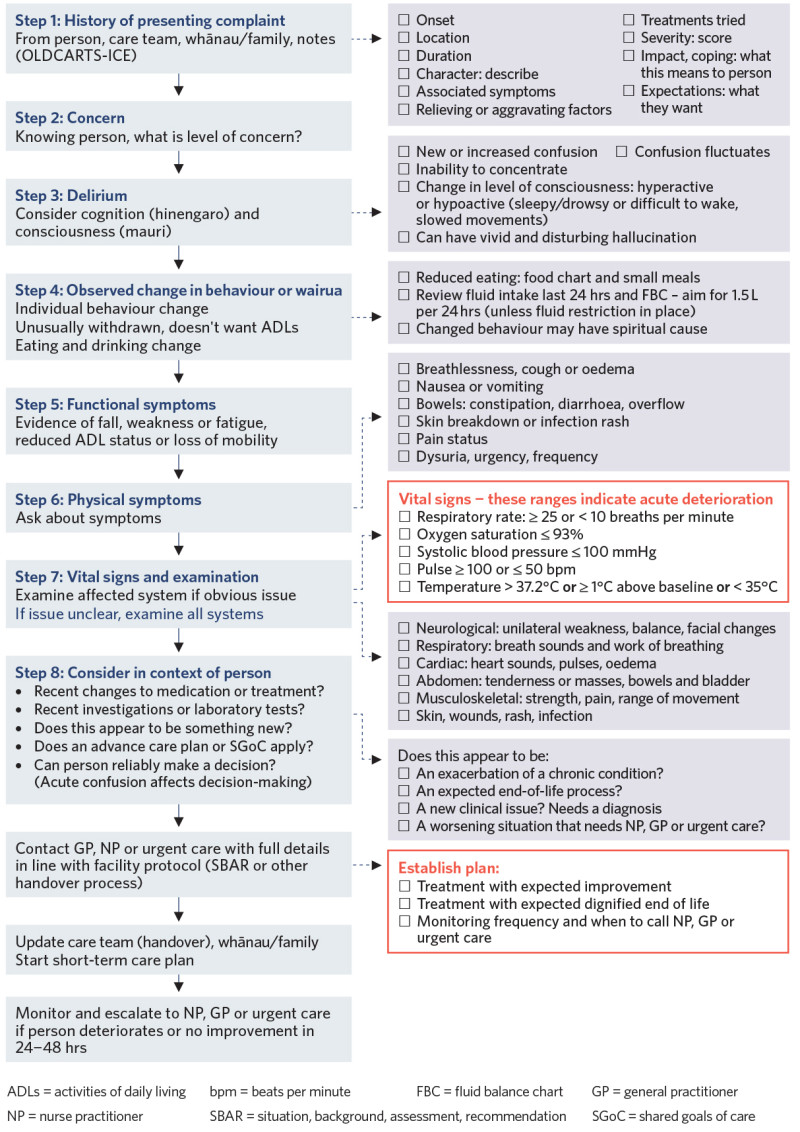

Step: 1

Domain: History of presenting complaint

Assessment:

- Use available resources (staff, whānau/family, notes) to understand a full history of presenting complaint (OLDCARTS-ICE).

Step: 2

Domain: Concern

Assessment:

- Changes can be subtle based on knowledge of person (staff, whānau/family). How concerned are you?

Step: 3

Domain: Delirium

Assessment:

- Consider hyper- and hypoactive delirium.

Note: Be aware that the person who is very quiet and drowsy or sleeping a lot may have hypoactive delirium.

Step: 4

Domain: Observed change in behaviour

Assessment:

- Are behaviours inconsistent with the person’s usual routines and habits?

- Unusually withdrawn or not wanting personal care support with activities of daily living?

- Eating: meals missed? Consider starting food chart.

- Drinking: how much has person drunk in last 24 hours?

- Consider fluid balance chart: aim for 1.5 L in 24 hours.

Step: 5

Domain: Functional symptoms

Assessment:

- Is there evidence or recent history of a fall?

- Is there evidence of weakness or fatigue such as:

- a change in activities of daily living

- a loss of mobility?

Step: 6

Domain: Physical symptoms

Assessment:

- Cardiorespiratory: Any breathlessness, cough, oedema?

- Gastrointestinal: Is there any abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting?

- Review bowel chart: Is there evidence of constipation, diarrhoea, overflow?

- Skin: Any breakdown, infections, rash, sores?

- Pain: Review pain status

- Genitourinary: Any dysuria, urgency, frequency?

Step: 7

Domain: Vital signs and examination

Assessment:

Measure vital signs and compare with baseline. A change from baseline is important even if this sits in the ‘normal range’ (American Medical Directors Association 2003).

Values of concern are:

- respiratory rate: > 25 or < 10 breaths per minute

- oxygen saturation < 93%

- systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg

- pulse > 100 or < 50 bpm

- temperature > 37.2°C or > 1°C above baseline or < 35°C.

Examine the relevant system or systems:

- neurological: unilateral weakness, balance, facial changes

- respiratory: breath sounds and work of breathing

- cardiac: heart sounds, pulses, oedema

- abdomen: tenderness or masses, bowels and bladder

- musculoskeletal: strength, pain, range of movement

- skin, wounds, rash, infection.

Step: 8

Domain: Consider in context of person

Assessment:

Any recent changes to medication or treatment plans?

Any recent investigations or laboratory tests?

Decision-making:

- Is this primarily a clinical decision? (New acute presentations need a diagnosis.)

- Does an advance care plan or directive apply?

- Is the person able to participate in decision-making? (Delirium reduces a person’s decision-making capacity.)

Does this appear to be:

- an exacerbation of a chronic condition

- an expected end-of-life process

- a new clinical issue

- a worsening situation that needs NP, GP or urgent care review?

Vital signs associated with acute deterioration

The research has not reached a consensus on normal physiological ranges for older adults living in ARC (Daltrey et al 2022; Reyes et al 2018). Comparison with baseline is recommended when assessing for deterioration as the degree of change may be more important than the absolute number recorded (American Medical Directors Association 2003). The following trigger points are based on the available evidence:

- respiratory rate: > 25 or < 10 breaths per minute

- oxygen saturation: < 93%

- temperature:

- > 37.2°C or 1°C above baseline (Sloane et al 2014) or

- > 37.2°C (twice) or > 37.8°C (once) or > 1°C over baseline (Centers for Disease Control 2023)

- < 35°C (hypothermia often indicates sepsis in ARC)

- blood pressure: systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg

- heart rate (pulse): > 100 or < 50 beats per minute.

Acute deterioration decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Responding to acute deterioration

Responses to acute deterioration include the following.

- Communicate the situation to NP, GP or urgent care.

- Research shows handover tools such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) provide effective support for clear and accurate clinical communication (Müller et al 2018).

- The SBAR framework from Pathway Health (nd) can help with assessing and handing over the clinical situation.

- Develop a short-term care plan that includes prescribed actions and nursing interventions.

-

Collaborate with NP or GP to establish the type and frequency of monitoring and threshold for further escalation if the older person gets worse or fails to improve.

- Fully inform the older person, whānau/family and/or enduring power of attorney about the situation and plan.

- Complete effective handover: provide information the team needs to understand the situation and care plan for the acute event until it is resolved.

- Sign off the short-term care plan once situation is resolved.

- Update long-term care plan if the person’s overall health has changed.

Treatment

Nursing interventions are critical to the quality of care the older person and their whānau/ family experience. That applies whether the interventions are aimed at the person’s recovery from an acute event or a safe, comfortable and dignified end-of-life process.

Nursing interventions include:

- spiritual care (comfort, support, person-centred care)

- nutrition and hydration

- skin care

- positioning and mobility (avoiding bed rest and deconditioning in anticipation of recovery)

- use of appropriate PRN medication

- monitoring the person and updating NP/GP if the person deteriorates, becomes distressed or fails to show expected signs of improvement in 24—48 hours.

References | Ngā tohutoro

American Medical Directors Association. 2003. Acute Change of Condition in the Long Term Care Setting: Clinical Practice Guideline (1st ed). Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association.

bpacnz. 2015. The immediate management of acute coronary syndromes in primary care. Best Practice Journal 67. URL: bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/April/coronary.aspx.

Boockvar K, Brodie HD, Lachs M. 2000. Nursing assistants detect behavior changes in nursing home residents that precede acute illness: development and validation of an illness warning instrument. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48(9): 1086–91. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04784.x.

Centers for Disease Control. 2023. Healthcare-associated Infection Surveillance Protocol for Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Events for Long-term Care Facilities. National Healthcare Safety Network Healthcare Association. URL: www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/ltc/ltcf-uti-protocol-current.pdf.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. 2013. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet 381(9868): 752–62. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9.

Daltrey JF, Boyd ML, Burholt V, et al. 2022. Detecting acute deterioration in older adults living in residential aged care: a scoping review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 23(9): 1517–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.05.018.

Kojima G, Iliffe S, Walters K. 2018. Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing 47(2): 193–200. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afx162.

Laging B, Kenny A, Bauer M, et al. 2018. Recognition and assessment of resident deterioration in the nursing home setting: a critical ethnography. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27(7–8): 1452–63. DOI: 10.1111/ jocn.14292.

Müller M, Jürgens J, Redaèlli M, et al. 2018. Impact of the communication and patient hand- off tool SBAR on patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open 8(8): e022202. DOI: 10.1136/ bmjopen-2018-022202.

Ouslander JG, Perloe M, Givens JH, et al. 2009. Reducing potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: results of a pilot quality improvement project. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 10(9): 644–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.07.001.

Pathway Health. nd. Pathway INTERACT®. INTERACT® Tools Library. URL: pathway-interact. com/interact-tools/interact-tools-library/.

Reyes B, Chang J, Vaynberg L, et al. 2018. Early identification and management of sepsis in nursing facilities: challenges and opportunities. Journal of American Medical Directors Association 19: 465–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.04.004.

Sepsis Trust NZ. nd. Have an infection? Just ask 'could it be sepsis'. URL: sepsis.vitalcolour.co.nz/ wp-content/uploads/SepsisTrustNZ-Brochure.pdf.

Sloane PD, Kistler C, Mitchell CM, et al. 2014. Role of body temperature in diagnosing bacterial infection in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62(1): 135–40. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.12596.

Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. 2018. Frailty trajectories to identify end of life: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Medicine 16(1): 171. DOI: 10.1186/s12916-018-1148-x.

Sund-Levander M, Tingström P. 2013. Clinical decision-making process for early nonspecific signs of infection in institutionalised elderly persons: experience of nursing assistants. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 27(1): 27–35. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00994.x.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.