Approach to breathlessness (dyspnoea) | Tūngāngā (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Breathlessness (dyspnoea) is the difference between the demand to breathe and the ability to breathe (Mahler 2017). To observe it, watch how hard a person works to catch their breath (work of breathing) and count the number of breaths per minute. It is a frightening symptom and has a significant impact on how a person feels and functions.

Key points

- People with dyspnoea are more likely to be admitted to hospital than those with other symptoms (Johnson et al 2016).

- Common causes of breathlessness in older adults are (Mahler 2017):

- respiratory (infection or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

- cardiac (heart failure, myocardial infarction, angina)

- anaemia

- psychological (anxiety, panic)

- imminent end of life (predicted/diagnosed dying).

Why this is important

Breathlessness is a strong predictor of mortality (Mahler 2017). It tends to increase in the last few months of life regardless of condition and is an indicator of worsening health and reduced survival (Johnson et al 2016). It is common in older people and often has cardiac or respiratory causes (van Mourik et al 2014).

Implications for kaumātua*

Breath and breathing are significant in Māori culture. Te reo Māori has several words for breath, many of which link breath and breathing to te taiao (the natural world) and to Māori creation stories. While these cultural constructs do not change the occurrence, cause or treatment of breathlessness, it is important to understand them because experiencing breathlessness may contribute to anxiety or wairua (spiritual) unrest (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua guide for more information).

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

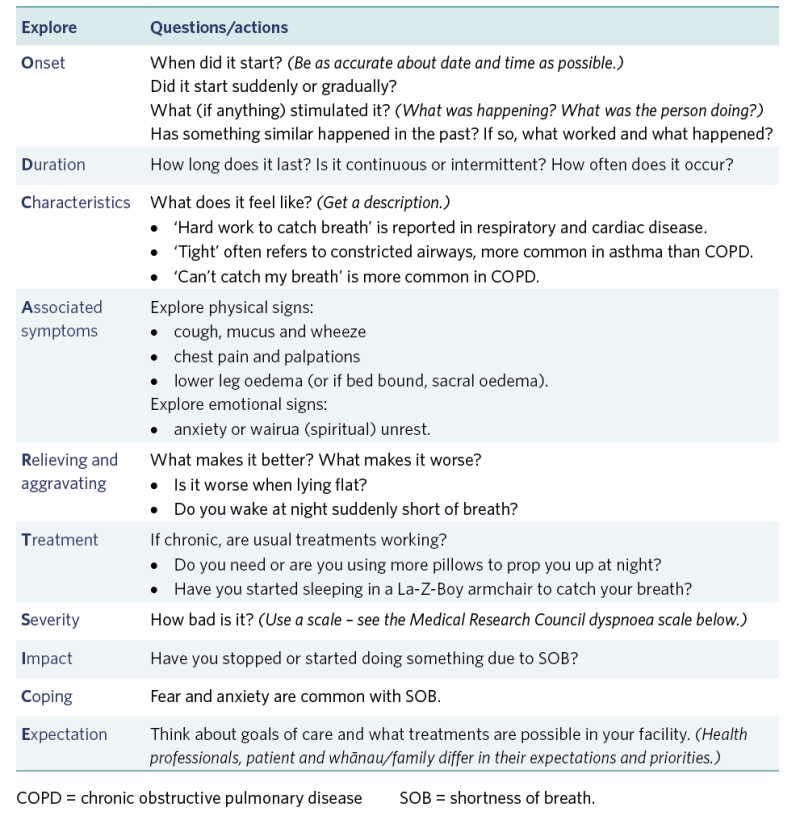

Use a tool to gather a systematic and structured report of breathlessness. It is helpful to use OLDCARTS-ICE (adapted from Bickley 2017) selectively when exploring breathlessness.

OLDCARTS-ICE

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Assessment tool for chronic breathlessness specifically

The Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale is a widely used rating scale with five levels (van Mourik et al 2014):

- Breathless with strenuous exercise

- Short of breath when hurrying on the level or up a slight hill

- Walking slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness

- Stopping for breath after walking 100 metres or after a few minutes on the level

- Too breathless to leave the house.

Treatment

Minimise risk of developing breathlessness

- Offer immunisations (influenza, COVID-19, pneumococcal).

- Use infection prevention and control measures (minimise exposure to others with respiratory illness).

- Support safe swallow techniques and positioning (refer for swallow deficits).

- Manage frailty.

- Support correct use of prescribed medications and inhaler technique.

Manage respiratory medication

- For inhaled medication, regularly review patient’s technique and equipment.

- For anti-anxiety medication, support its use along with non-pharmacological interventions.

- Discuss with prescriber and patient the use of opioids for managing respiratory drive.

- For diuretic therapy, closely monitor body weight.

Care planning

A patient-centred approach to chronic breathlessness is recommended. Prioritise daily activity. Use the multidisciplinary team and whānau/family to address impacts of and impact on breathlessness, including physiological, psychological, whānau/family and spiritual aspects.

Non-pharmacological approaches include:

- listening to the person’s concerns

- engaging whānau/family and spiritual support

- encouraging distraction and relaxation through music, reading and diversional therapy

- keeping the person moving at a level appropriate to them (from walking to repositioning in bed)

- supporting them to eat well, as maintaining strength and eating favourite foods improves mood

- supporting sleep

- providing person-specific complementary therapies such as massage, aromatherapy and/or pet therapy

- providing culturally informed complementary therapies such as te ao Māori

- breathing exercises (Hikitia te Hā: www.allright.org.nz/tools/hikitia-te-ha) and/or waiata (singing) to promote breath control

- whānau/family or a cultural advisor may recommend other therapies.

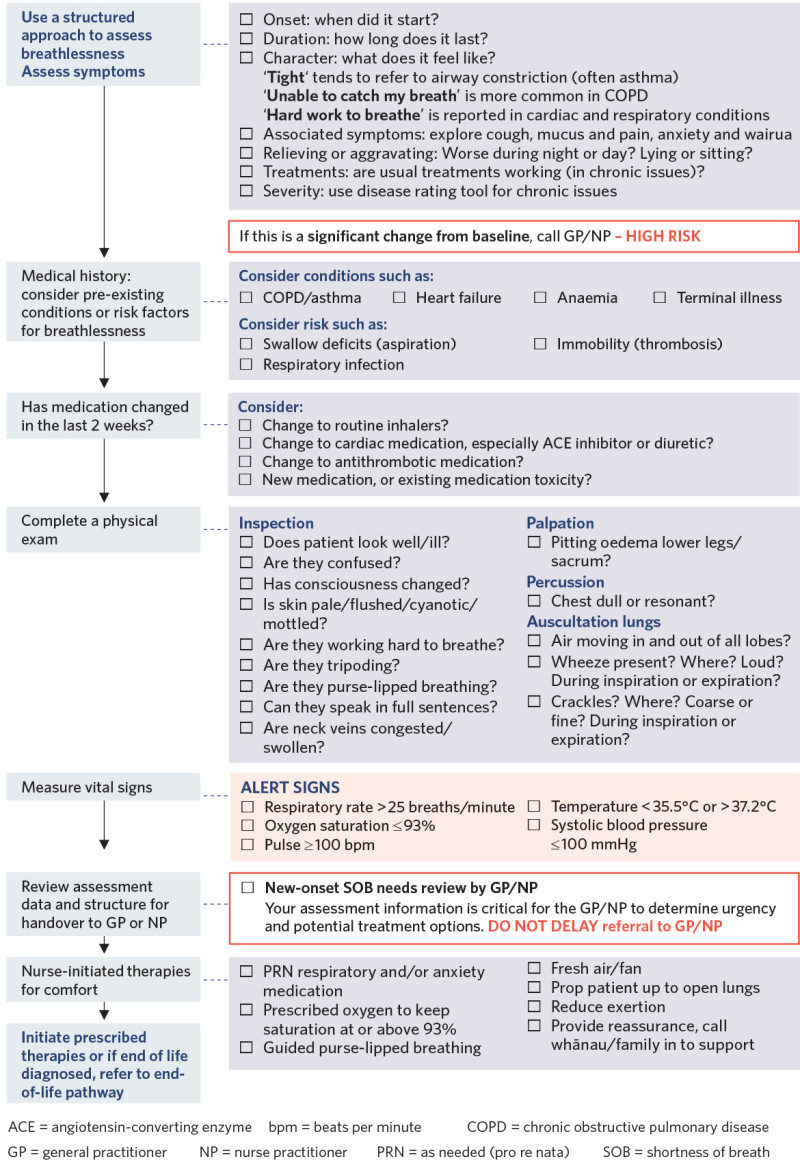

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Bickley LS. 2017. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking (12th North American ed). URL: www.amazon.com/Bates-Physical-Examination-History-Taking/dp/146989341X.

Johnson MJ, Bland JM, Gahbauer EA, et al. 2016. Breathlessness in elderly adults during the last year of life sufficient to restrict activity: prevalence, pattern, and associated factors. Journal of American Geriatric Society 64(1): 73–80. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.13865.

Mahler DA. 2017. Evaluation of dyspnea in the elderly. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 33(4): 503–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.cger.2017.06.004.

van Mourik Y, Rutten FH, Moons KGM, et al. 2014. Prevalence and underlying causes of dyspnoea in older people: a systematic review. Age and Ageing 43(3): 319–26. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afu00.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.