Communicating effectively with older people and their whānau/family | Kia kōrerorero pai ki ngā kaumātua me ō rātou...

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Care planning

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Effective communication is a dynamic two-way process that allows parties to exchange ideas, thoughts, knowledge, emotion and meaning in a way that they both understand (Wanko Keutchafo et al 2020). In health care, person-centred communication aims to engage older people and their whānau/families in decision-making about care planning and evaluation (Kwame and Petrucka 2021). Being respectful and recognising the person as a whole are at the centre of this process. When health professionals hear what is important to the person, it helps that person feel safe and listened to in their own home.

Why this is important

Effective communication recognises the person’s experiences, stories and knowledge and respects their values, preferences and culture (Kwame and Petrucka 2021). It positively impacts on the person’s self-esteem and feelings of control (Davis et al 2022). Research has also shown that listening and responding to whānau/family concerns reduces adverse events in health care (Gerdik et al 2010; Health Quality & Safety Commission 2017).

Implications for kaumātua*

Māori culture has very proud oral traditions, including oral histories through waiata (song), whakataukī (proverbs), whakapapa (genealogy) and pūrākau (stories), as well as through kōrero (speaking). Te reo Māori (the Māori language) is rich with kupu whakarite (metaphors) and is considered almost poetic. These language-related cultural influences continue to shape the communication styles Māori use today in some ways.

Kaumātua and whānau/family may use figurative language or other communication in which they imply the meaning rather than state it directly. They may also communicate from a place of politeness with the result that, because they are eager to be polite and not be a nuisance, they under-report issues and refrain from asking questions to clarify issues (Graham and Masters-Awatere 2020). It is important to take these cultural differences into account when communicating with kaumātua and their whānau/family.

At a time of illness or when navigating challenges, kaumātua may wish to have support with communication. Someone who is important to them, such as a whānau/family member, minister, neighbour or friend, may be best placed to provide this support. At the time of admission, it is important to establish who the support person is and update records if the person in this role changes.

Creating a connection is central to effective and meaningful communication with Māori and their whānau/family (Oetzel et al 2014; Wilson et al 2021). One way to achieve this is to use whanaungatanga, which means sharing information on a more personal level, outside of your clinical role (Wilson et al 2021). This helps form a connection that provides a foundation for open, two-way communication based on mutual respect and trust.

Due to the collective nature of Māori culture, it is important that kaumātua and whānau/ family have a sense of being heard. Upholding the mana (dignity, prestige, esteem) of the kaumātua and their whānau/family throughout communication is important. You can do this by understanding that:

- it is important to include kaumātua in meetings even if they no longer appear to understand

- traditionally, direct eye contact could indicate a challenge, leading to conflict, so kaumātua may look away or even close their eyes during conversations (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information).

* Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Communicating with older people in care situations

Address barriers and facilitators to person-centred communication before you begin (Kwame and Petrucka 2021).

| Barriers | Facilitators |

| Time restriction | Stop, give the person your attention and create time to address the issue. Options for creating time range from setting time in the immediate future for a simple one-on-one conversation to booking an appointment that works for staff, resident and whānau/family. The sooner you form relationships and address issues, the less likely it is that communication issues will occur. |

| Task focused | Make communication the task. |

| Language differences | Have a translator in place (people often prefer independent translators). |

| Resident health status | Pick the best time of day or moment in the resident’s health journey for discussion. |

| Sensory loss | Communicate in a quiet (no background noise), private environment with hearing and visual aids in place (about one-third of people in residential care have visual and hearing deficits) (Yamada et al 2014). |

| Cognitive impairment | Have whānau/family members present. Use short sentences and closed or simple questions, and reduce distractions. Having a person they trust present can help a resident with cognitive impairment feel safe. |

| Religious or cultural | Find out about cultural and religious needs and match your communication to them. |

Models of effective communication

Use meaningful connections to support effective communication (above) (Wilson et al 2021).

Source: cpcr.aut.ac.nz/our-research (Reused with permission)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

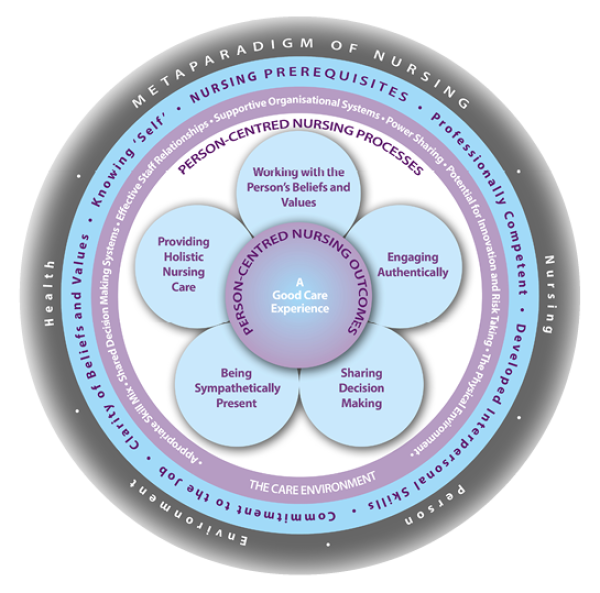

Use a person-centred framework such as McCance et all (2011) to support effective communication (above).

Source: www.cpcpr.org/resources (Reused with permission)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Holistic care, engagement and presence

- Attend to the conversation, display warmth and be genuinely interested (ie, don’t multitask; make the time for this conversation).

- Ask the resident about their physical and emotional health; be curious.

- Recognise and acknowledge the resident’s view of their health.

-

Be honest when answering a question about illness, using language that the resident can understand. (Be honest if you don’t know the answer to the question.)

- Be genuine: your non-verbal communication should match what you say.

- Use appropriate humour.

- Use respectful terms and approaches.

- Use appropriate methods of communication with people with memory issues.

- Keep conversations short and to the point.

- Provide reference information for the person and their whānau/family.

- Have a support person present as often as possible.

- Minimise distractions.

- Use pictures, objects and gestures to support your words.

- Write down key messages as memory prompts.

- Focus on keeping the person feeling safe.

Shared decision-making – communicating with whānau/families

Researchers (Bélanger et al 2018) suggest families want help to be involved in the care of their loved ones. In particular, they want to:

- understand issues about the person's condition through:

- having scheduled access to the general practitioner or nurse practitioner

- having a defined contact person to liaise with

- being included in clinical decisions so they understand risks and benefits

- participate in care and need:

- structured information on how to help

- written and verbal information on care and management issues

- recognition of their knowledge of the person’s personal preferences and habits.

Care planning

It is useful to record in the care plan the communication preferences (frequency and method) of the person, their whānau/family and/or delegated decision-maker so that you are more likely to meet their expectations. Matters these preferences may relate to include, but are not limited to:

- routine communication (eg, newsletters, health updates or reports about routine reviews for the person and/or their delegated decision-makers)

- teleconferencing tool (eg, Zoom, Messenger)

- preferred telephone contact (by mobile or landline, at home or work)

- what information they are happy to receive by text

- preferred form of written information, such as by email (and at what primary email address) or hard copy

- social media preferences and restrictions, such as:

- access to social platforms such as Facebook

- sharing protocols

- recording (voice, video or photographs).

References | Ngā tohutoro

Bélanger L, Desmartis M, Coulombe M. 2018. Barriers and facilitators to whānau/family participation in the care of their hospitalized loved ones. Patient Experience Journal 5(1): 56–65. DOI: 10.35680/2372- 0247.1250.

Davis L, Botting N, Cruice M, et al. 2022. A systematic review of language and communication intervention research delivered in groups to older adults living in care homes. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 57(1): 182–225. DOI: 10.1111/1460-6984.12679.

Gerdik C, Vallish RO, Miles K, et al. 2010. Successful implementation of a whānau/family and patient activated rapid response team in an adult level 1 trauma center. Resuscitation 81(12): 1676–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.06.020.

Graham R, Masters-Awatere B. 2020. Experiences of Māori of Aotearoa New Zealand’s public health system: a systematic review of two decades of published qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44(3): 193–200. DOI: 10.1111/1753-6405.12971.

Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2017. Kōrero mai: Patient, family and whānau escalation of care. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. URL: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/resources/resource-library/patient-family-and-whanau-escalation-process-case-for-change/.

Kwame A, Petrucka PM. 2021. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nursing 20(1): 158. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2.

McCabe C. 2004. Nurse–patient communication: an exploration of patients’ experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing 13(1): 41–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x.

McCance T, McCormack B, Dewing J. 2011. An exploration of person-centredness in practice. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 16(2): manuscript 1. DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No02Man01.

Oetzel J, Simpson M, Berryman K, et al. 2014. Managing communication tensions and challenges during the end-of-life journey: perspectives of Māori kaumātua and their whānau. Health Communication 30(4): 350–60. DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2013.861306.

Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B. 2017. The development and testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory – Staff (PCPI-S). International Journal for Quality in Health Care 29(4): 541–7. DOI: 10.1093/ intqhc/mzx066.

Wanko Keutchafo EL, Kerr J, Jarvis MA. 2020. Evidence of nonverbal communication between nurses and older adults: a scoping review. BMC Nursing 19: 53. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-020-00443-9.

Wilson BJ, Bright FAS, Cummins C, et al. 2021. ‘The wairua first brings you together’: Māori experiences of meaningful connection in neurorehabilitation. Brain Impairment 1–15. DOI: 10.1017/BrImp.2021.29.

Yamada Y, Vlachova M, Richter T, et al. 2014. Prevalence and correlates of hearing and visual impairments in European nursing homes: results from the SHELTER study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 15(10): 738–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.012.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.