To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Decision support

- Further resources

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in older people. It is not a normal part of ageing. It is a serious disabling mood disorder that can affect the way a person feels, behaves and thinks.

It causes distress and anxiety, impacts on functional ability, reduces physical activity and can cause memory problems. Depression induces thoughts of worthlessness, helplessness and suicidal ideation (Blackburn 2017; Zenebe et al 2021).

Key points

- Studies suggest about 30 percent of older people worldwide have depression (Hu et al 2022; Zenebe et al 2021).

- Depression is underdiagnosed in older people (Zenebe et al 2021).

- Depression can lead to suicide. Around the world, older adults have the highest rate of suicide among all age groups (De Leo 2022; Stanley et al 2016).

Why this is important

Depression increases the risk of mortality and negatively impacts on quality of life (Sivertsen et al 2015).

Implications for kaumātua*

Depression impacts on every aspect of kaumātua wellbeing, including their spiritual and physical health and their connection with whānau/family as well as their mental health. For kaumātua, the experience of depression may involve more spiritual unease, unrest or disturbances so you need to interpret their behaviour carefully (bpacnz 2010). People with cultural knowledge or whānau/family may be helpful in recognising these culturally specific manifestations.

Complementary, culturally informed interventions to address depression may include karakia (prayer) and/or pure (cleansing rituals).

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Maintaining wellness for Māori (Russell 2018)

Concepts for maintaining wellness are not unique to kaumātua. However, having a strong sense of connection and cultural identity is a cornerstone of their mental wellbeing. Key aspects include:

- whakawhanaungatanga and belonging (connections with the people that are important to them, being able to manaaki [take care of or look after] others)

- feeling positive about life (having a sense of purpose, hope, things to look forward to, feeling connected)

- cultural connectedness (Māori culture is important to Māori, but not all Māori feel connected to their culture and need help to reconnect)

- cultural identity (a secure cultural identity comes from cultural and social connection).

See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

Assessment

Diagnosis of depression (Truschel 2022) DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Major depressive disorder includes five or more of the following symptoms that last more than 2 weeks. At least one of those symptoms should be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

The symptoms are:

- depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

- markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day

- significant weight loss when not dieting, weight gain or a decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day

- a slowing down of thought and a reduction of physical movement (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down)

- fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day

- diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day

- recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for dying by suicide.

Risk factors for depression (Maier et al 2021; Sivertsen et al 2015; Zenebe et al 2021)

- Female sex

- Increasing age

- Being single or divorced

- Bereavement/grief or loss

- Loneliness/social isolation

- Chronic illness or poor health

- Chronic pain

- Cognitive impairment

- Loss of function

- Loss of independence

- History of depression

- Childhood traumatic experiences

- Multiple medications

- Addiction (alcohol, drug, prescribed medication)

- Relocating to a residential care environment

Risk factors for suicide (De Leo 2022)

- Older men over 80 years of age

- Chronic pain

- Functional dependence

- Loneliness and feelings of abandonment

- Loss of meaning in life

- Frailty (Bickford et al 2021; Shah et al 2022)

Screening

Geriatric depression scale (short form)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

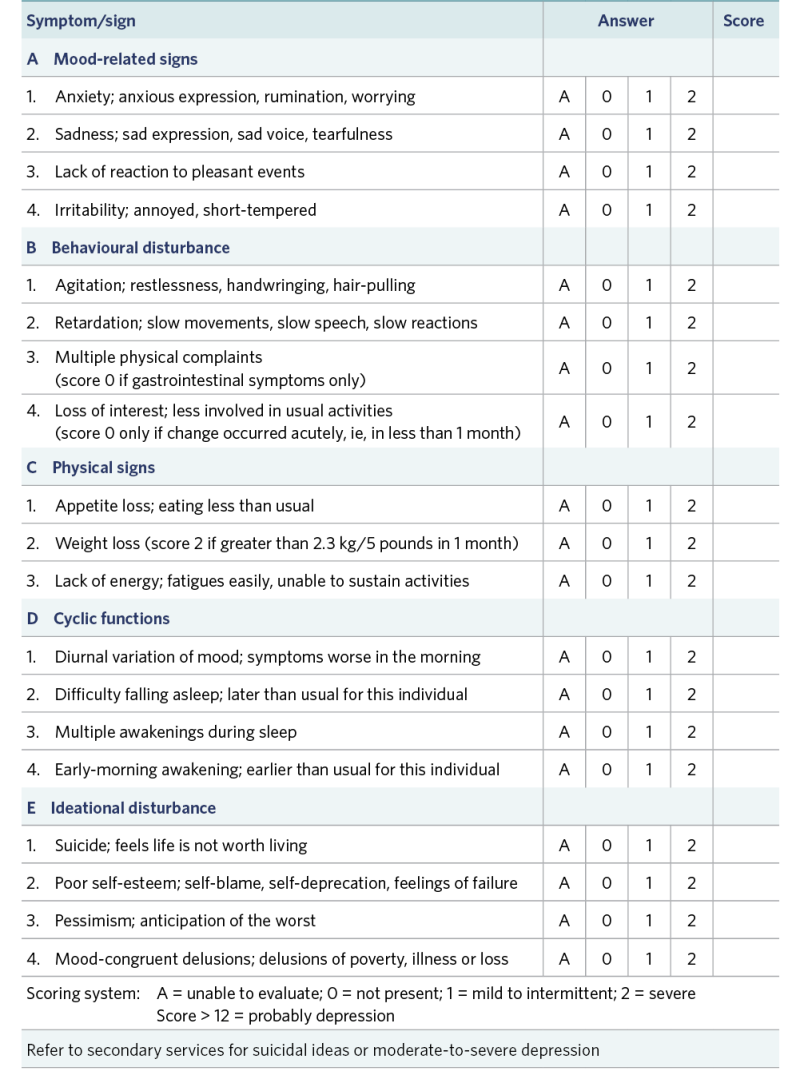

Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (more reliable for people with increasing levels of cognitive impairment)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

Good evidence indicates that a non-pharmacological approach alone or in combination with antidepressant therapy is effective treatment for depression. There is limited evidence that pharmacological therapy alone protects people from suicide (De Leo 2022).

Psychotherapy approaches

- Undertake life review, a process of recalling, evaluating and assigning meaning to personal memories. It may involve talking only or may include using photographs and images to stimulate thinking. Research shows conversation improves psychological wellbeing (Al-Ghafri et al 2021).

- Provide cognitive behavioural therapy with a trained facilitator. It helps the person reinterpret situations and events and come up with solutions to them (Blackburn 2017). New Zealand research specific to use with Māori is available (Bennett et al 2016).

- Provide social support and encourage participation in social activities (Shah et al 2022).

- Recognise risk of depression or suicidal ideation and refer to specialist services for help (Holm et al 2021).

- Connect people living in care with volunteers from the community (developing social support bonds) (Gleeson et al 2019).

Physical therapy

- Participating in regular exercise of moderate intensity, including aerobic and strength- based training, has a positive impact on depression in older people (Schuch et al 2016). Culturally appealing activities such as kapa haka (Māori performing arts) may encourage participation (Nikora et al 2022).

- Physical activity is considered protective and so is also recommended for those who do not have depression (Bigarella et al 2022; Maier et al 2021).

- It has a positive impact on people with suicidal ideation (Stanley et al 2016).

Pharmacology

Antidepressants are usually started at a low dose and increased over 1 to 2 months. They require regular monitoring for efficacy, adverse effects and ongoing need.

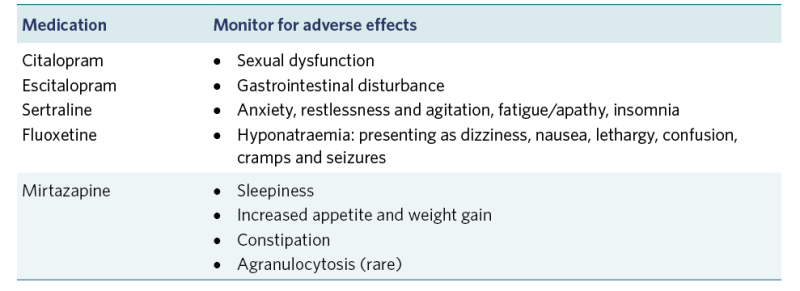

First-line treatments (bpacNZ 2017)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

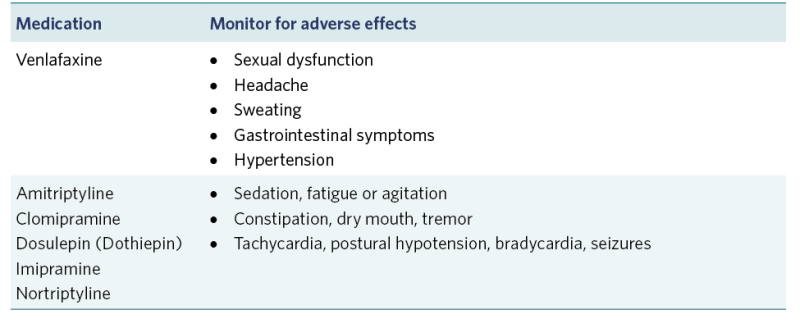

Second-line treatments (bpacNZ 2017)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

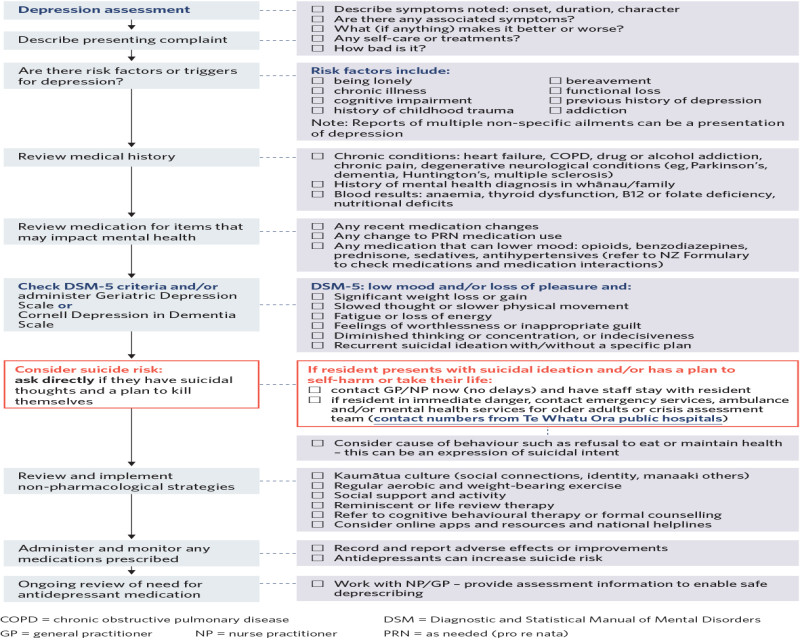

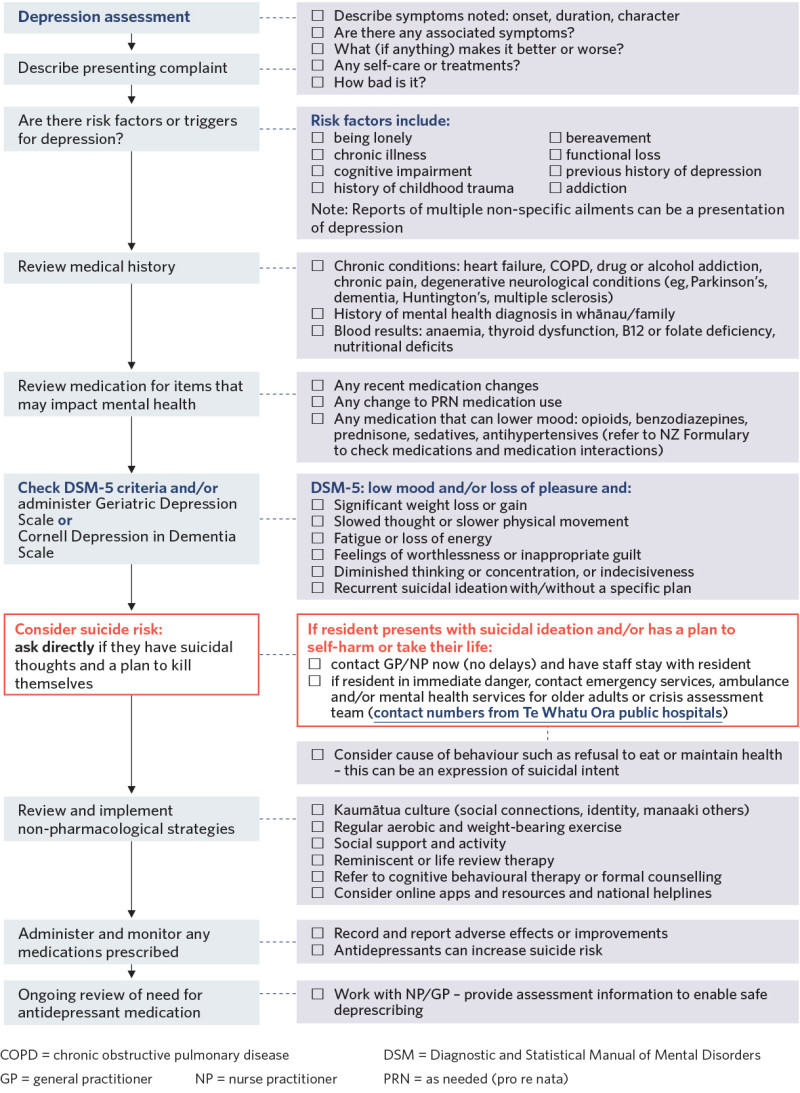

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Further resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Depression is not a normal part of growing older. URL: www.cdc.gov/aging/depression/index.html.

National Institute on Aging. Depression and older adults. URL: www.nia.nih.gov/health/depression-and-older-adults.

Te Hiringa Hauora | Health Promotion Agency. Māori | Depression and anxiety. URL: depression.org.nz/get-better/your-identity/maori.

References | Ngā tohutoro

l-Ghafri BR, Al-Mahrezi, A, Chan MF. 2021. Effectiveness of life review on depression among elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan African Medical Journal 40: 168. DOI: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.168.30040.

Bennett ST, Flett RA, Babbage DR. 2016. Considerations for culturally responsive cognitive-behavioural therapy for Māori with depression. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 10: e8. DOI: 10.1017/prp.2016.5.

Bickford D, Morin RT, Woodworth C, et al. 2021. The relationship of frailty and disability with suicidal ideation in late life depression. Aging & Mental Health 25(3): 439–44. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1698514.

Bigarella LG, Ballotin VR, Mazurkiewicz LF, et al. 2022. Exercise for depression and depressive symptoms in older adults: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Aging & Mental Health 26(8): 1503–13. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1951660.

Blackburn P. 2017. Depression in older adults: diagnosis and management. British Columbia Medical Journal 59(3): 171–7. URL: bcmj.org/articles/depression-older-adults-diagnosis-and-management.

bpacnz. 2010. Recognising and managing mental health problems in Māori. Best Practice Journal 28: 8–17. URL: bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2010/June/mentalhealth.aspx.

bpacnz. 2017. The role of medicines in the management of depression in primary care. Best Practice Journal. URL: bpac.org.nz/2017/docs/depression2017.pdf.

De Leo D. 2022. Late-life suicide in an aging world. Nature Aging 2(1): 7–12. DOI: 10.1038/s43587-021-00160-1.

Gleeson H, Hafford-Letchfield T, Quaife M, et al. 2019. Preventing and responding to depression, self- harm, and suicide in older people living in long term care settings: a systematic review. Aging & Mental Health 23(11): 1467–77. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1501666.

Holm AL, Salemonsen E, Severinsson E. 2021. Suicide prevention strategies for older persons: an integrative review of empirical and theoretical papers. Nursing Open 8(5): 2175–93. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.789.

Hu T, Zhao X, Wu M, et al. 2022. Prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 311: 114511. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114511.

Maier A, Riedel-Heller SG, Pabst A, et al. 2021. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+: a systematic review. Plos One 16(5): e0251326. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251326.

Nikora LW, Meade R, Hall M, et al. 2022. The Value of Kapa Haka: An overview report. Auckland: Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. URL: www.maramatanga.ac.nz/media/7049/download.

Russell L. 2018. Te Oranga Hinengaro: Report on Māori Mental Wellbeing. Results from the New Zealand Mental Health Monitor & Health and Lifestyles Survey. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency | Te Hiringa Hauora.

Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, et al. 2016. Exercise for depression in older adults: a meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials adjusting for publication bias. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 38(3): 247–54. DOI: 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1915.

Shah J, Kandil OA, Mortagy M, et al. 2022. Frailty and suicidality in older adults: a mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology 68(5): 571–7. DOI: 10.1159/000523789.

Sivertsen H, Bjørkløf GH, Engedal K, et al. 2015. Depression and quality of life in older persons: a review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 40(5–6): 311–39. DOI: 10.1159/000437299.

Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, et al. 2016. Understanding suicide among older adults: a review of psychological and sociological theories of suicide. Aging & Mental Health 20(2): 113–22. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1012045.

Truschel J. 2022. Depression Definition and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria. URL: www.psycom.net/depression/major-depressive-disorder/dsm-5-depression-criteria.

Zenebe Y, Akele B, W/Selassie M, et al. 2021. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of General Psychiatry 20(1): 55. DOI: 10.1186/s12991-021-00375-x.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.