Leg ulcer care | Te maimoatanga o te kōmaoa o te waewae (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why leg ulcers are important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Wound characteristics

- Treatment

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Leg ulcers are chronic lower-leg wounds that do not heal in an expected and timely manner. Leg ulcers tend to start with trauma but are a result of underlying damage to veins, arteries or both. Venous leg ulcers are the most common (40–85 percent) followed by those with arterial aetiology (5–30 percent), mixed venous and arterial ulcers (10–20 percent) and other causes (5–25 percent). It is not uncommon for all leg ulcer types to take 6 months or more to heal (Harding et al 2015).

Key points (Carville 2012)

- The gold standard treatment for venous leg ulcers is compression therapy. Before that can occur, a full diagnostic work-up is required. Only health professionals with specialist knowledge and skills should apply full compression therapy.

- Arterial leg ulcers generally require specialist diagnostic tests and often surgical intervention to resolve the underlying cause.

- Mixed leg ulcers (with both venous and arterial causes) also require specialist review.

Why leg ulcers are important

Leg ulcers cause pain and disability and can reduce quality of life. They require specialist assessment for optimum outcomes.

Implications for kaumātua*

Māori have a holistic view of health and wellbeing, so it is important to treat the ‘whole person’ rather than just ‘the hole in the person’. The Māori cultural principles of mana (dignity, prestige, status), tapu (sacred, prohibited, restricted) and noa (neutral, ordinary, unrestricted) apply to leg ulcer care, just as they do to wound assessment. Observing these principles upholds the mana of kaumātua and contributes to providing holistic care (see the Wound assessment guide for a more detailed explanation).

It is important to give kaumātua and their whānau/family all the information they need to participate in treatments such as compression therapy, leg exercises and elevation (Jull et al 2018). Leg ulcers heal slowly, can be large and/or malodorous and may be a source of whakamā (shame, embarrassment) for kaumātua. Be particularly aware of the risk that some kaumātua may under-report pain due to whakamā.

Whānau/family may have culturally informed interventions that support wound treatment from a holistic perspective. These may include using rongoā Māori (traditional Māori medicines) and in some cases pure (cleansing rituals). Explore these options on an individual, case-by-case basis.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Venous leg ulcers develop when pressure in lower-limb veins increases, most often due to damaged vein valves. When these valves are damaged, blood flows back towards the ankle and the pressure in the vein increases, causing oedema and fragile blood capillaries and skin. If trauma occurs in this situation, it is likely to lead to leg ulceration (Hughes and Balduyck 2022).

Arterial leg ulcers develop where damaged or blocked arteries result in decreased blood flow to tissue. Skin can break down after trauma or spontaneously. Some leg ulcers have both venous and arterial causes.

Key point

- If new lower-leg wounds fail to heal or make significant progress in 6 weeks, consider a referral to a wound care service for diagnosis and treatment planning. Specialist services complete a full assessment, including ankle brachial pressure index to determine aetiology and develop an associated treatment plan.

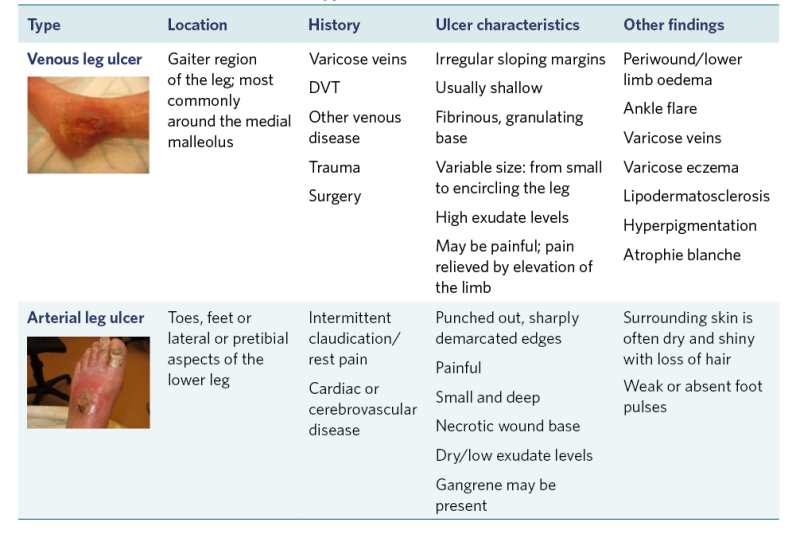

Wound characteristics (Harding et al 2015)

Table 1: Characteristics of the main types of chronic lower-limb wounds

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

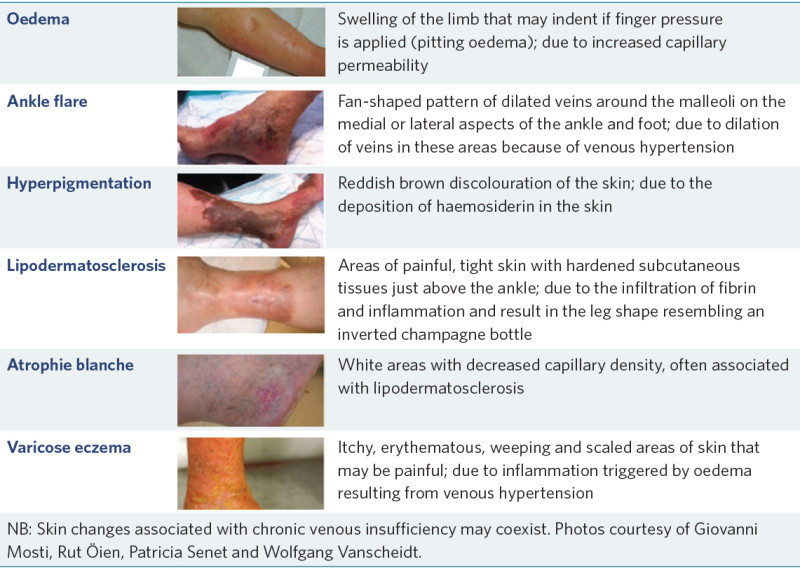

Table 2: Lower-leg changes associated with venous hypertension and chronic venous insufficiency

Source: Harding et al (2015)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

- Arterial leg ulcers often require surgical intervention, so referral to specialist services is required.

- For venous leg ulcers and some mixed ulcers, compression therapy is the gold standard treatment. This requires specialist assessment and training. Do not use compression therapy without a formal assessment from an appropriately qualified wound specialist; it could increase risk of ischaemia.

- There are multiple modes of compression therapy that wound specialist services can advise on and provide. Service provision varies, so contact your local Te Whatu Ora district for more information (New Zealand Wound Care Society 2013b).

- Compression hosiery can be prescribed to help prevent the development of venous leg ulcers in at-risk people and to avoid recurrence of healed ulcers. The patient wears it during the day. You can remove it overnight but should reapply it before the person’s feet touch the floor to avoid leg swelling, which makes application difficult. Slack (worn-out) hosiery will not work correctly; to access a replacement, make a referral to the prescribing wound service (New Zealand Wound Care Society 2013a).

References | Ngā tohutoro

Carville K. 2012. Wound Care Manual (6th ed, revised and expanded). Perth: Silver Chain Foundation.

Harding K, Dowsett C, Fias L, et al. 2015. Simplifying Venous Leg Ulcer Management: Consensus recommendations. London: Wounds International. URL: www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/simplifying-venous-leg-ulcer-management-consensus-recommendations.

Hughes M, Balduyck B. 2022. Made easy: challenges of venous leg ulcer management. Wounds International April. URL: https://woundsinternational.com/made-easy/made-easy-challenges-venous-leg-ulcer-management/.

Jull A, Slark J, Parsons J. 2018. Prescribed exercise with compression vs compression alone in treating patients with venous leg ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatology 154(11): 1304–11. DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3281.

New Zealand Wound Care Society. 2013a. Preventing venous leg ulcers. www.nzwcs.org.nz/images/luag/vlu_patient_info-Preventing-VLU-2013.pdf.

New Zealand Wound Care Society. 2013b. Treating venous leg ulcers. www.nzwcs.org.nz/images/luag/vlu_patient_info-Managing-VLU-2013.pdf.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.