To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Content

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Decision support

- Assessing for potential causes of syncope or collapse

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023

Definition

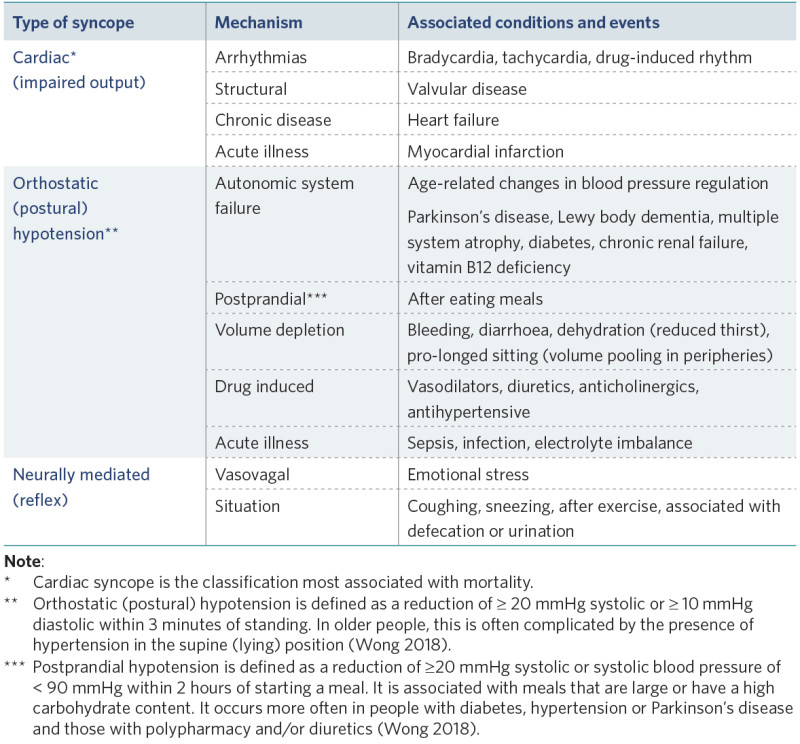

Syncope is a sudden transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion, followed by spontaneous complete recovery, in a short period of time. There are three types: cardiac; orthostatic (postural) hypotension; and neurally mediated, also known as reflex syncope (Runser et al 2017; Thiruganasambandamoorthy et al 2020).

Collapse (also known as ‘pseudo-syncope’) is a sudden loss of consciousness due to causes that do not create cerebral hypoperfusion. In these cases, recovery time may be slower. Examples of causes of collapse include epileptic seizure, hypoglycaemia, hypoxia and poisoning.

Key points

- Clinically, syncope and collapse present in the same way and require the same initial response. It is the assessment of likely causes that separates the conditions.

- Frail older people are more susceptible to syncope, are less likely to have syncopal warning signs (prodrome) and often do not recall the event (Pirozzi et al 2013).

- Syncope causes falls. However, not all falls are due to syncope (Wong 2018).

Why this is important

Recurrent syncope has a negative effect on reported quality of life (McCarthy et al 2020). While syncope may have a simple reversible cause, it can also be a sign of a serious underlying condition (Runser et al 2017).

Implications for kaumātua*

Because a loss of consciousness can be frightening, it is important to take a holistic approach to assessing the impact of the syncopal episode on kaumātua. This may include finding out how they are feeling ā wairua (spiritually), ā tinana (physically) and ā hinengaro (mentally and emotionally). Kaumātua may experience whakamā (shame, embarrassment) related to syncope and may not report syncopal episodes to avoid burdening anyone else (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information).

It is essential to provide kaumātua and whānau/family with all the information they need to understand the approach to assessing and treating syncope. You can support them by:

- including whānau/family in conversations

- providing whānau/family with opportunities to share their observations and insights and valuing their input

- setting aside enough time to discuss matters with all parties involved

- thoroughly discussing and explaining decision-making about any changes in the plan of care (eg, medication changes, investigations).

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family . It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

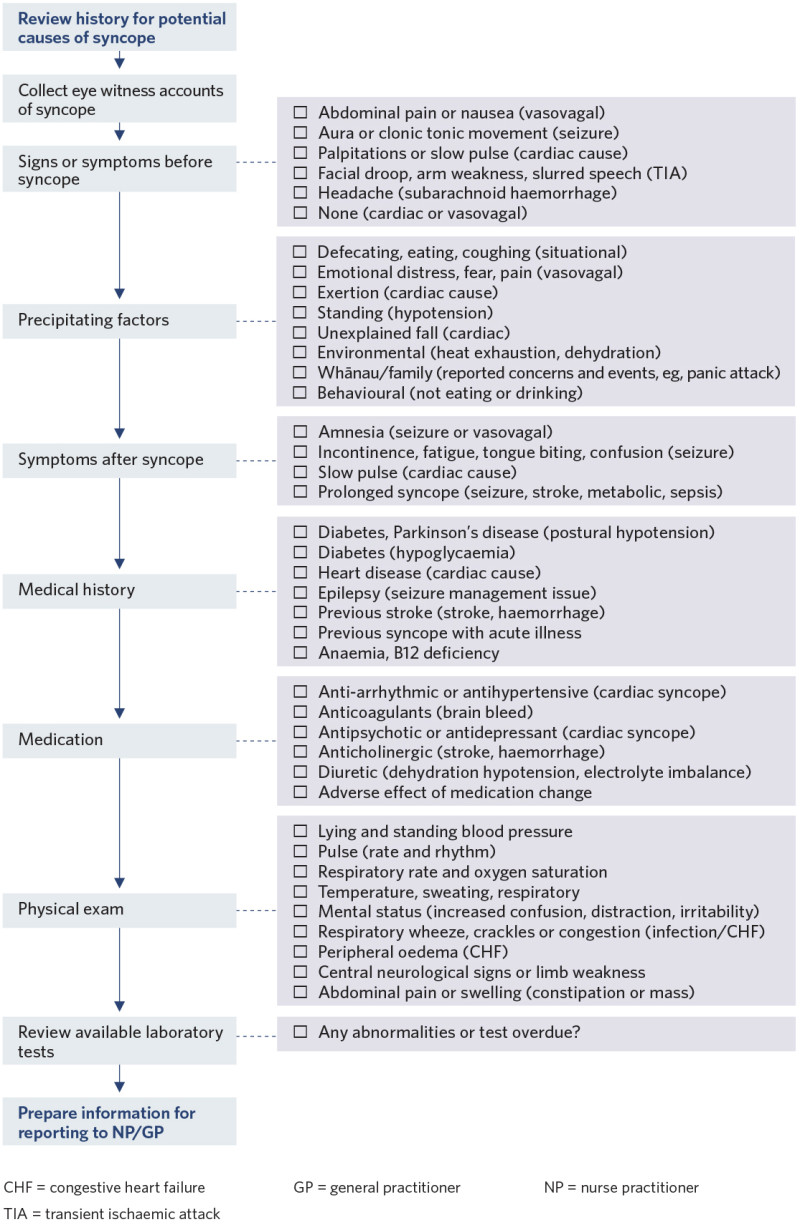

A recommendation is to take a standardised approach to syncope, including in responding to the situation and taking a thorough history and physical exam (Runser et al 2017).

Among the three general syncope classifications (Pirozzi et al 2013), research suggests that cardiac and orthostatic syncope are the most frequent types in older people (de Ruiter et al 2018; Wong 2018). However, many factors can contribute to syncope and/or collapse (Wong 2018).

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

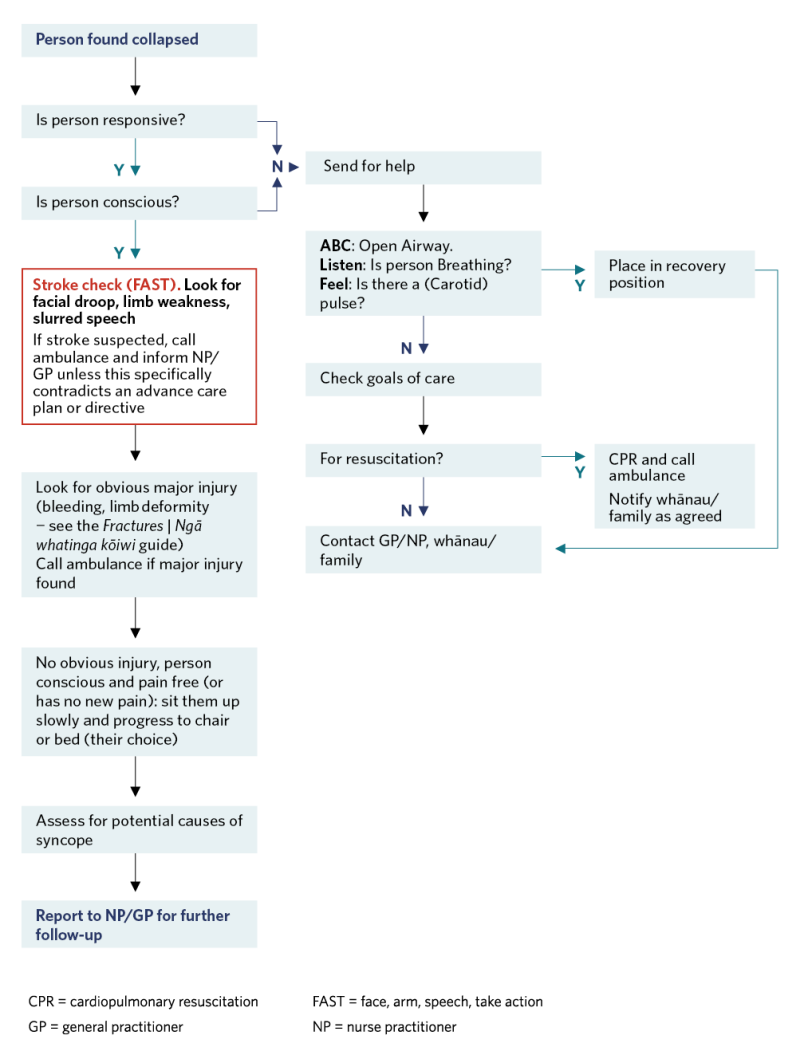

Treatment focuses on the initial response and on finding a reason for the loss of consciousness (see the 'Decision support' section). It is important to be aware of the person’s advance care planning preferences when responding to syncope or collapse.

Orthostatic hypotension treatments (Palma and Kauffman 2020)

Non-pharmacological treatments

- Maintain activity as much as possible.

- Avoid simple sugars, alcohol and coffee.

- Bolus 500 ml water can raise blood pressure (lasts less than 1 hour).

- Change position slowly.

- Reduce blood pooling by elevating legs, leg exercises (toe raises, thigh contraction), physical activity (avoid prolonged sitting) and compression garments such as abdominal binders.

- Sleep with head of bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees.

- Possibly increase salt in diet – but only in discussion with general practitioner or nurse practitioner.

Pharmacological

- Access medication review for drugs that worsen hypotension (diuretic, antihypertensive, alpha-blockers) and potential treatments.

- Provide anaemia treatment.

Decision support

Responding to syncope or collapse

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Assessing for potential causes of syncope or collapse

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

de Ruiter SC, Wold JFH, Germans T, et al. 2018. Multiple causes of syncope in the elderly: diagnostic outcomes of a Dutch multidisciplinary syncope pathway. Europace 20(5): 867–72. DOI: 10.1093/ europace/eux099.

McCarthy K, Ward M, Romero Ortuño R, et al. 2020. Syncope, fear of falling and quality of life among older adults: findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging (TILDA). Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 7: article 7. DOI: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00007.

Palma J, Kaufmann H. 2020. Management of orthostatic hypotension. Continuum: Lifelong learning in neurology 26(1): 154–77. DOI: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000816.

Pirozzi G, Ferro G, Langellotto A, et al. 2013. Syncope in the elderly: an update. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics 4(3): 69–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcgg.2013.07.001.

Runser LA, Gauer RL, Houser A. 2017. Syncope: evaluation and differential diagnosis. American Family Physician 95(5): 303–12.

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. 2020. Multicenter emergency department validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Internal Medicine 180(5): 737–44. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0288.

Wong CW. 2018. Complexity of syncope in elderly people: a comprehensive geriatric approach. Hong Kong Medical Journal 24(2): 182–90. DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176945.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.