Overall, the rate of dispensing of five or more long-term medicines has increased since 2019. Rates are higher for Pacific peoples, Māori and those aged 85 and over

- 46.5 percent of people aged 65 years and over received five or more long-term medicines (defined as five or more of the same chemicals dispensed over two consecutive quarters). 33.3 percent of people received 5 to 7 long-term medications, 17.9 percent of people received 8 to 10 long-term medications and 8.1 percent of people received 11 or more long-term medications (noting that these groups are not mutually exclusive).

- The rate of people dispensed five or more long-term medicines increased significantly with age, from 36.7 percent among those aged 65–74 years to 69.2 percent among those aged 85 years and over. The rate of older people receiving 11 or more long-term medicines increased sharply with age: 13.9 percent of those aged 85 years and over received 11 or more medicines, nearly 2.5 times the rate of those aged 65–74 years (5.7 percent).

- Rates varied significantly by ethnic group. Māori and Pacific peoples received more medicines at a younger age compared with those identifying as Asian or European/Other. For example, among the younger cohort (aged 65–74 years), Pacific peoples (10.9 percent) and Māori (9.1 percent) were more likely than other ethnic groups – Asian (5.7 percent) and European/Other (5.0 percent) – to receive 11 or more medications over two consecutive quarters in 2023.

- Rates also varied by district, ranging from 49.7 percent to 60.4 percent among those aged 75–84 years.

Table 1 shows the percentage and count by age group and ethnic group of those dispensed five or more long-term medicines.

Table 1: People dispensed five or more long-term medicines, by age group and ethnic group, 2023

| Ethnic Group |

Age group (years) |

| 65–74 |

75–84 |

85+ |

| % |

count |

% |

count |

% |

count |

| Māori |

47.2 |

39,497 |

63.4 |

8,831 |

69.6 |

1,971 |

| Pacific peoples |

55.2 |

18,277 |

65.5 |

4,910 |

64.0 |

1049 |

| Asian |

35.7 |

47,063 |

55.5 |

9,961 |

64.9 |

3,394 |

| European/Other |

34.7 |

353,581 |

54.5 |

125,523 |

69.6 |

56,732 |

Table 2: People aged 65 years and over receiving five or more long-term medicines, by age, New Zealand, 2023

| |

Age % |

| 65–74 |

75–84 |

85 and over |

Total |

| Dispensed five or more long-term medicines |

36.7 |

55.3 |

69.2 |

46.5 |

| 5–7 long-term medicines |

27.5 |

38.8 |

46.7 |

33.3 |

| 8–10 long-term medicines |

12.8 |

22.1 |

30.9 |

17.9 |

| 11 or more long-term medicines |

5.7 |

10.3 |

13.9 |

8.1 |

| Note: these groups are not mutually exclusive. |

Table 3: People aged 65 years and over receiving five or more long-term medicines, by ethnic group, 2023

| |

Long-term medicines dispensed (%) |

| Ethnic group |

Five or more |

5–7 |

8–10 |

11 or more |

| Māori |

52.3 |

35.5 |

21.9 |

10.5 |

| Pacific peoples |

58.5 |

37.8 |

25.5 |

12.2 |

| Asian |

42.9 |

29.6 |

16.6 |

7.9 |

| European/Other |

45.8 |

33.4 |

17.3 |

7.7 |

‘Triple whammy’ dispensing in people aged 65 years and over has significantly decreased since 2019 – about 3,500 fewer individuals.

The triple whammy is the combination of an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), a diuretic and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

Medsafe notes an increased risk of acute kidney injury with this combination, especially in people with risk factors for renal failure and in older adults.[5] The combination should be avoided if possible.

- Of those aged 65 years and over, 2.7 percent were dispensed the triple whammy within the same 90-day period. This equates to 21,750 people in 2023. The rate has significantly decreased from 2019 (3.4 percent), which is about 3,500 fewer people.

- Rates varied significantly by ethnic grouping; for example, among those aged 65–74 years Māori (3.6 percent) and Pacific peoples (3.4 percent) were significantly higher than Asian (1.8 percent) or European/Other (2.7 percent). Rates were lowest among older people aged 85 years and over across all ethnic groups.

- Females were more likely to be dispensed triple whammy in the same 90-day period when compared to males. This pattern is consistent across all age groups.

- Rates also varied significantly by district; for example, among those aged 75–84 years, rates varied by more than 2.5-fold, ranging from 2.1 to 5.5 percent.

- This indicator does not include those who bought an NSAID over the counter or had a prescription in a previous period.

Antipsychotic and benzodiazepine or zopiclone dispensing increases significantly with age

In older people, certain classes of medicines carry a substantially higher risk of adverse effects. Two examples presented in this Atlas domain are antipsychotics and a benzodiazepine or zopiclone. Common adverse effects include impaired functional ability, agitation, confusion, blurred vision, urinary retention, constipation, postural hypotension and falls. These increase if both classes of medicine are taken together. This indicator cannot assess inappropriate use of these medicines; however, high rates of prescribing may indicate misuse or overuse.

- The dispensing of psychotropic agents increases with age. For example, 13.5 percent of 65–74 year olds received a benzodiazepine or zopiclone in 2023 compared with 25.8 percent of those aged 85 and over.

- Benzodiazepine or zopiclone is more commonly used (16.2 percent) than an antipsychotic (4.9 percent) and, since 2019, dispensing rates of both classes have remained steady.

- Antipsychotic dispensing rates are significantly higher for Māori across all age groups compared with other ethnicities. Rates also varied by district; for example, among those aged 85 years and over, rates ranged more than twofold – from 8.1 percent to 16.9 percent.

- Benzodiazepine or zopiclone dispensing rates are significantly higher among European/Other populations at all ages. Among those aged 85 years and over, 26.3 percent of European/Other individuals were dispensed these medicines, compared to 19.6 percent of Asian, 18.3 percent of Māori, and 9.4 percent of Pacific peoples. Rates also varied significantly by district.

- Females were more likely to be dispensed benzodiazepine or zopiclone when compared to males. This pattern is consistent across all age groups.

- The rate of combined use of antipsychotics and benzodiazepine or zopiclone was relatively low (2.1 percent) but increased with age—from 1.3 percent among those aged 65–74 years to 6.0 percent among those aged 85 years and over.

Psychotropic medication increases the risk of falling [6] and there is evidence that reducing psychotropic medication can result in no or limited worsening of key outcomes such as sleep quality or behavioural problems.[6, 7] The most recent Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR report) shows that in 2023, the rate remains high at around 22 per 1,000 in this age group, confirming that hip fractures continue to be a major burden among older adults [8].

Polypharmacy in Aged Residential Care (ARC)

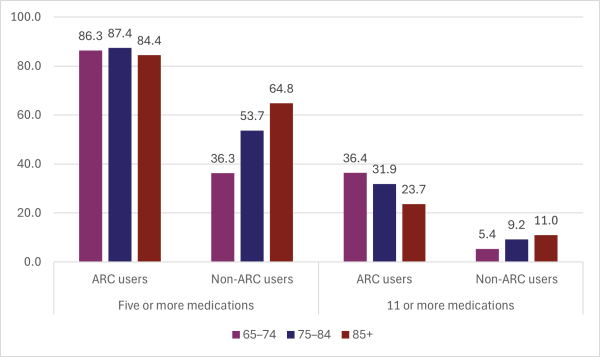

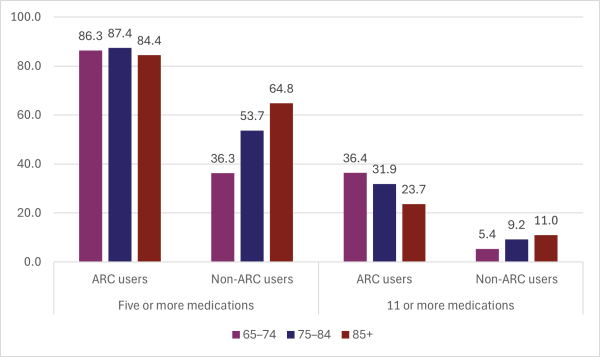

Our analysis showed significant differences in the dispensing of multiple medications between people who lived in aged residential care (ARC) and those who didn’t, in 2023:

- 86 percent of people living in aged residential care were dispensed five or more medications in two consecutive quarters, compared to 45 percent of people not living in aged residential care

- 28 percent of ARC residents were dispensed 11 or more medications, compared to 7.1 percent of people not living in aged residential care.

For age-specific rates, please refer to Figure 1.

Figure 1: Polypharmacy rates in people living in aged residential care and those not living in aged residential care, by age group (percent), 2023

What questions might the data prompt?

It is pleasing to see the reduction in ‘triple whammy’ dispensing since 2019. Key findings from this update include high dispensing rates of 11 or more medications – particularly among those aged 85 years and over – and notable differences between people living in aged residential care and those who are not. These findings warrant further investigation.

- Why do we see such high rates of polypharmacy (11+ medications) among people in aged residential care? How much of this is driven by guideline-based prescribing versus clinical complexity and multimorbidity?

- How do similar districts compare?

- Why are Māori and Pacific peoples receiving more medications at younger ages? Could earlier onset of multiple comorbidities in some groups drive multiple medications from the outset?

- Why are greater proportions of European/Other people aged 65 years and over dispensed a benzodiazepine or zopiclone than Māori or Pacific peoples?

- How often are medications reviewed or deprescribed, particularly after hospital discharge or in aged care settings?

What tools or frameworks can support safe deprescribing in ARC settings?

- Are there any strategies for practitioners to minimise harm from deprescribing (eg, decompensation in heart failure) while also avoiding harm from overprescribing?

- What role might secondary clinicians have in influencing prescribing patterns in their community?