Opioids atlas domain

The opioids domain of the Atlas of Healthcare Variation gives an overview on the dispensing of opioids by demographics and health district to identify areas of wide variation.

The opioids domain of the Atlas of Healthcare Variation gives an overview on the dispensing of opioids by demographics and health district to identify areas of wide variation.

| Opioid atlas single map | Opioid atlas PHO analysis |

This update uses data from 2023. We have used primary health organisation (PHO) enrolment data as the denominator, replacing Stats NZ estimated population projections. This resulted in 3,678 people being excluded from the Atlas. This is less than 4 percent of the total count of 99,663 people dispensed a strong opioid in a year. There were no significant differences in the percent excluded due to not being enrolled by age, ethnicity or gender.

The methodology report has more information on the indicators, data sources, definitions and rationale we used to gather this data.

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (PDF 570KB)

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (DOCX 330KB)

Opioids are a type of medicine used to treat pain. They are used a lot in hospital for patients to help ease pain but can also cause harm.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) classes opioids as one of four groups of medicines (along with anticoagulants, insulin and sedatives) that can cause harm to patients, even when used as intended.

Opioid analgesia is the primary intervention for managing pain in hospital patients. Opioids are also considered effective treatment for severe pain in palliative care. [1] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [1] recommends opioids should not be used for neuropathic pain without specialist assessment. There is limited evidence that opioids are effective for treating chronic non-cancer pain in the long term. [2]

Our analyses showed that strong opioid dispensing has increased over time, particularly among older adults. We also found that older adults were more likely to be dispensed strong opioids for six or more weeks. Long-term use of opioids should be used with extreme caution and the potential for serious adverse effects and complications be considered. [1,3]

Harm associated with opioid therapy include opioid tolerance, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, [4] iatrogenic addiction and dependency, drug diversion and aberrant drug-related behaviours. [1,5] In addition, a strong relationship between severe dependence on opioids and other substance use and mental health disorders has been observed.[6]

Health practitioners considering opioid therapy for chronic non-malignant pain are advised to conduct a thorough benefit-to-harm evaluation to determine whether opioids are the most appropriate option. This evaluation should include a detailed history, physical examination, and diagnostic assessment prior to initiating treatment, with ongoing review throughout the course of therapy.[1,7]

There is growing evidence showing that hospital encounters are a key trigger for opioid prescribing, especially in younger populations. [8] Our analysis also showed that nearly one in six young people who were dispensed a strong opioid went to hospital in the eight days prior to dispensing.

There is a concern whether even short-term opioid use can lead to prolonged exposure, especially if there is no clear plan to reassess the need for opioids or taper off them if necessary. [8] It underscores the need for targeted interventions at hospital discharge to ensure opioids are used safely, appropriately, and temporarily.

Opioid analgesia is the primary intervention for managing pain in hospital patients. Opioids are also considered effective treatment for severe pain in palliative care. [1] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [1] recommends opioids should not be used for neuropathic pain without specialist assessment. There is limited evidence that opioids are effective for treating chronic non-cancer pain in the long term. [2]

Our analyses showed that strong opioid dispensing has increased over time, particularly among older adults. We also found that older adults were more likely to be dispensed strong opioids for six or more weeks. Long-term use of opioids should be used with extreme caution and the potential for serious adverse effects and complications be considered. [1,3]

Harm associated with opioid therapy include opioid tolerance, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, [4] iatrogenic addiction and dependency, drug diversion and aberrant drug-related behaviours. [1,5] In addition, a strong relationship between severe dependence on opioids and other substance use and mental health disorders has been observed.[6]

Health practitioners considering opioid therapy for chronic non-malignant pain are advised to conduct a thorough benefit-to-harm evaluation to determine whether opioids are the most appropriate option. This evaluation should include a detailed history, physical examination, and diagnostic assessment prior to initiating treatment, with ongoing review throughout the course of therapy.[1,7]

There is growing evidence showing that hospital encounters are a key trigger for opioid prescribing, especially in younger populations. [8] Our analysis also showed that nearly one in six young people who were dispensed a strong opioid went to hospital in the eight days prior to dispensing.

There is a concern whether even short-term opioid use can lead to prolonged exposure, especially if there is no clear plan to reassess the need for opioids or taper off them if necessary. [8] It underscores the need for targeted interventions at hospital discharge to ensure opioids are used safely, appropriately, and temporarily.

Selected findings from the Atlas are summarised below. For all indicators and detailed commentary, see the Atlas dashboards, where you can search by age, ethnic group, year, and health district.

A ‘weak’ opioid is classed as step 2 of WHO’s analgesic ladder. This includes tramadol, codeine and dihydrocodeine. These opioids are subsidised in New Zealand. Paracetamol with codeine is excluded because it contains a low dose of codeine.

A ‘weak’ opioid is classed as step 2 of WHO’s analgesic ladder. This includes tramadol, codeine and dihydrocodeine. These opioids are subsidised in New Zealand. Paracetamol with codeine is excluded because it contains a low dose of codeine.

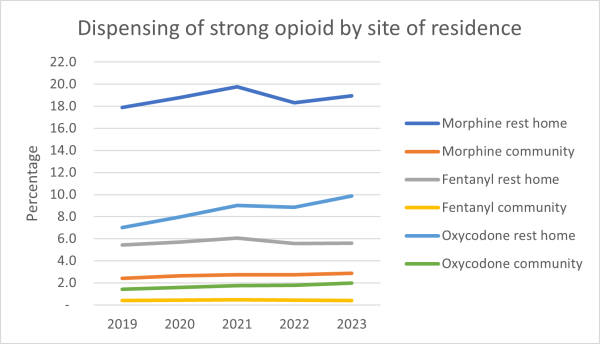

In previous years we noticed a high rate of morphine dispensing among people aged 65 and over living in aged residential care (ARC). In contrast, the rate of morphine dispensing by people aged 65 and over not living in ARC is not increasing at the same rate.

We explored what is causing the increase in aged residential care.

One of the most likely reasons for the difference could be the use of strong opioids for palliative care. Morphine is the recommended first-line opioid in palliative care.

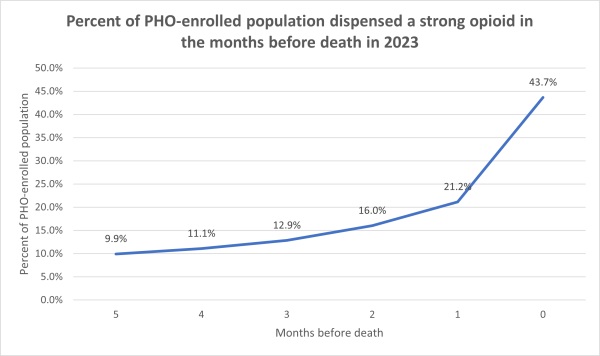

Dispensing strong opioids by type in the six months prior to a person’s death was also analysed. The graph below shows that strong opioid dispensing rates peak in the month of death, with 43.7 percent of people receiving a strong opioid in their last month of life.

Further analyses showed that 49.7 percent of aged residential care residents and 37.9 percent of people not living in aged residential care were dispensed a strong opioid in their last month of life.

Overall, in 2023, 55.9 percent of those in aged residential care and 43.0 percent of people not living in aged residential care were dispensed a strong opioid at some point in their last six of months of life.

Data for this Atlas domain was drawn from the Pharmaceutical Collection, which contains claim and payment information from community pharmacists for subsidised dispensing. This collection does not allow for analysis of patients’ condition or the effectiveness of dose provided. This means it’s not possible to assess the appropriateness or otherwise of prescribing.

Unsubsidised dispensing is not included in this analysis; nor does it indicate if people took the medicine.

This analysis focuses on the number of people dispensed opioids, not on the number of prescriptions of these medicines. We have used this approach because interpreting what the number of dispensed prescriptions might mean is complicated by differences in prescribing frequency, formulation and dose, and if the medicine is to be taken ‘as needed’ or at regular times.

We recommend further local analysis of the people receiving these medicines that accounts for these factors and the person’s clinical condition.

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (PDF 570KB)

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (DOCX 330KB)

Key findings from this update of the Opioids Atlas, which incorporates data through 2023, were discussed with clinicians to better understand potential drivers behind the increase in opioid dispensing. While strong opioids dispensing among older adults is high, this does not necessarily reflect inappropriate prescribing. Patterns appear to be a combination of clinical necessity (eg, comorbidities limiting alternatives), compassionate care priorities (comfort over long-term risk) and concerns about under-treating pain.

Our data shows that around 10 percent of strong opioids are dispensed for six or more weeks, and the rate has not substantially changed since 2019. However, high rates in people aged 80 and over and wide district variation (up to eight-fold variation in oxycodone dispensing) raise questions that warrant further exploration:

Data for this Atlas domain was drawn from the Pharmaceutical Collection, which contains claim and payment information from community pharmacists for subsidised dispensing. This collection does not allow for analysis of patients’ condition or the effectiveness of dose provided. This means it’s not possible to assess the appropriateness or otherwise of prescribing.

Unsubsidised dispensing is not included in this analysis; nor does it indicate if people took the medicine.

This analysis focuses on the number of people dispensed opioids, not on the number of prescriptions of these medicines. We have used this approach because interpreting what the number of dispensed prescriptions might mean is complicated by differences in prescribing frequency, formulation and dose, and if the medicine is to be taken ‘as needed’ or at regular times.

We recommend further local analysis of the people receiving these medicines that accounts for these factors and the person’s clinical condition.

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (PDF 570KB)

Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Methodology for opioids (DOCX 330KB)

Key findings from this update of the Opioids Atlas, which incorporates data through 2023, were discussed with clinicians to better understand potential drivers behind the increase in opioid dispensing. While strong opioids dispensing among older adults is high, this does not necessarily reflect inappropriate prescribing. Patterns appear to be a combination of clinical necessity (eg, comorbidities limiting alternatives), compassionate care priorities (comfort over long-term risk) and concerns about under-treating pain.

Our data shows that around 10 percent of strong opioids are dispensed for six or more weeks, and the rate has not substantially changed since 2019. However, high rates in people aged 80 and over and wide district variation (up to eight-fold variation in oxycodone dispensing) raise questions that warrant further exploration: